Coral Reef Growth is One of Nature's Wonders, Part 2

Part 2: Reef Structure and Zonation

Introduction

In Part 1, the basic progression by which coral reefs form was discussed. As the volcanic mountain building process unfolds on the oceans floor, islands rise and fall. The unyielding geological forces causing this upheaval also shape the coral reefs that form in the resulting shallows. The shape of the reef depends on its age, or rather, the life-stage of its island base. A number of distinct zones occur over the temporal and spatial extent of the reef. Even more important, this zonation affects the morphology and diversity of corals and other organisms associated with each respective area. Thus, every zone has a characteristic community structure dictated by abiotic (non-living) conditions such as depth, wave action, and the availability of sunlight.

It should be noted that the following descriptions are generalizations. Every reef has its own unique combination of conditions which affect its shape. For example, coral reefs in Bora Bora have been formed in virtually text-book pattern. On the other hand, in the Caribbean, atoll type reefs are exceedingly rare. In short, a multitude of factors goes into reef zonation. Nonetheless, every tropical coral reef on Earth will exhibit some, if not all, of the following sections.

Reef Zones

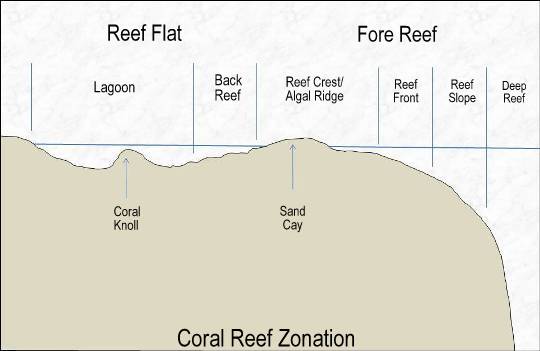

REEF FLAT: The reef flat complex comprises both the lagoon and the back reef zones. Both zones may have similar water quality conditions, owing to the shelter offered by the reef crest. The main differences include substrate conditions, which are sandy in the lagoon and rocky on the flat, as well as depth. Lagoons may be quite deep, while flats are typically very shallow. However, in many places sandy and rocky areas are highly interspersed, making it effectively irrelevant to distinguish one zone from the other.

LAGOON. The lagoons formed by barrier and atoll reefs may or may not be a viable area for coral growth. Over time, the sinking island can drop the sandy floor of the lagoon out of the photic zone, thereby eliminating it as coral habitat. If shallow, salinity and temperature fluctuations are dominant abiotic factors, especially since the outer reef areas restrict water flow through the lagoon. Moreover, lagoons associated with barrier reefs are also subject to nutrient-rich run-off from the adjacent landmass. Shallow lagoons present opportunities for coral types not available elsewhere. Here, patch reefs, coral knolls, and seagrass beds may punctuate the sand flats. Long-polyped scleractinians (LPS) can also survive in the less stable environment, as they are more robust to changes in water quality than other coral species.

BACK REEF. This part of the reef can be very extensive, sometimes being as wide as several thousand meters. Similar to the lagoon, the back reef area exhibits the highest environmental stochasticity (variability). Salinity and temperature fluctuations are greater here than on any other area of the reef. In fact, the reef flat may be as shallow as a few inches and can suffer prolonged exposure during low tide. The substrate varies from loose coral rubble to sand, which stays in place due to relatively low wave action and water flow. Interestingly, coral growth here is quite limited, yet the presence of numerous other types of macrofauna make the flat the most diverse area of the reef. Corals that do thrive here include pocilloporids and table acroporids, along with columnar and free-living species.

REEF CREST/ALGAL RIDGE. The reef crest is subject to the heaviest wind and wave action on the reef. As such, life here is tough and varies according to the severity of water conditions. In some cases small sand islands, called cays, may emerge at the crest. Sections exposed to air at low tide, and/or heavy waves, are dominated by encrusting algae. Where water conditions are more moderate, the reef crest exhibits coral growth in the form of encrusting and very stout branching morphologies. Submassive elkhorn corals are premier examples of this stoutly branched form. Other coral forms may include encrusting types with very little vertical dimensionality. In addition to being robust and strong, any corals living on or near the reef crest must be able to withstand intense solar radiation. In the interstitial spaces, crabs, shrimp, and snails find refuge from predators.

FOREREEF: The forereef area includes the reef front/buttress zone, the reef slope, and the deep reef. It should be noted, however, that forereef zones gradually transition into each other and there may be significant overlap from one section to the next. Coral growth on the forereef is highly diverse and extremely dense. This zone also holds the greatest variety of coral morphologies on the reef.

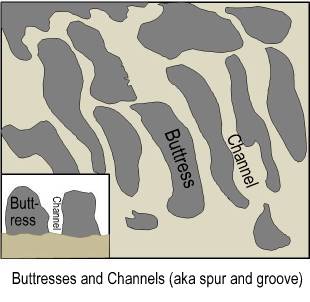

REEF FRONT/BUTTRESS ZONE. The reef front is subject to heavy wave action, and extends down to about 20 meters. Downward oriented channels alternate with coral spurs, or buttresses, all of which radiate outward. These formations are commonly referred to as spur and groove. In the interest of being completely accurate, however, there is some argument that spur and groove is an incorrect description of these occurrences. Though the terminology is widely used, they may be better described as buttresses and canyons.

The buttresses provide stability against strong waves, while the deep channels move debris and sediment away from the reef. These canyons may extend to depths of 30 meters or more, and typically have sandy bottoms. On the whole, this area is highly oxygenated and collects intense solar radiation. Biological communities on the reef front are mainly comprised of boulder corals, encrusting coralline algae, and a multitude of fish species. However, the vertical sides of the buttresses can provide good habitat for more delicate branching and soft corals. The deepest sections, near the sandy bottom, may show significant growth of plate-like corals, which are large but frail. The reef front may extend as far as 300 meters from the reef crest, making this zone an extensive and important part of the reef as a whole.

REEF SLOPE. The reef slope is the region which exhibits the most variable and densest coral communities. Water movement on the reef slope is still significant enough to scour detritus away, maintaining clear and clean conditions. The slope may be nearly vertical and for a short stretch (20-40 meters deep), the combination of reduced waves and available sunlight allows many species of delicate branched and soft corals to thrive. Every crack and crevice is inhabited by life, from the smallest invertebrates to large macrofauna like sharks, tunas, and shoals of tropical fish. The reef slope is the most quintessential part of the coral reef. Chances are, if you have seen pictures of SCUBA divers on a reef, or been the diver yourself, you have experienced the reef slope.

DEEP REEF. The deepest part of the reefthe outer edgeprovides habitat for very delicate plate corals, gorgonians/sea fans, and sea whips. As the sunlight dissipates into the abyss, hermatypic (reef-building) corals give way to ahermatypic corals. At a depth of about 150 meters, solar intensity is only 5% of that at the surface and coral photosynthesis can no longer occur. There are deep water coral communities which do not rely on photosynthesis for survival. Rather, they are dependant upon nutrients and food particles brought to them by water currents. They also depend on marine snow, which is essentially detritus falling from higher up in the water column. Deep water corals grow much more slowly than shallow water corals, perhaps only a few centimeters per year. Little is known about deep water coral communities because of their inaccessible nature. Few have been studied in detail, but technical advances in remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) are opening new avenues of study for these special environments.

Conclusion

There are very few places on Earth that can match coral reefs for diversity. Recent evidence suggests that coral reefs have contributed more species to the worlds oceans than all other marine provinces combined. Moreover, coral reefs are massive geological structures created by living organisms. There is nothing else in the world that can compare to the amazing reef-building process, nor its results. From an ecological perspective, coral reefs are one of the most valuable environments to have ever been studied. For more than 400 million years, corals have made their contributions to the marine environment. They have fascinated scientists and non-scientist alike since before the days of Charles Darwin. The more we learn about them, the more astounding they become. Simply put, there is nothing else like a coral reef.

Works Cited

Barley, Shanta. Coral Reefs are Most Fecund Cradles of Diversity. New Scientist: Life. 2001. URL: http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn18360-coral...

Castro, Peter and Michael E. Huber. Marine Biology, Fifth Edition. McGraw Hill: Boston. 2005.

Deep Water Corals, What are They? South Atlantic Fishery Management Council; Habitat and Ecosystem Section. 2010. URL: http://www.safmc.net/ecosystem/HabitatManagement/...

Goreau, Thomas. Poor Terminology in Coral Reef Research 2: Spur and Groove. 2006. URL: http://coral.aoml.noaa.gov/pipermail/coral-list/2...

Thurman, Harold V. and Alan P. Trujilo. Introductory Oceanography, Tenth Edition. Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River. 2004.

U.S. Department of Commerce; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. What are Coral Reefs. 2009. URL: http://coris.noaa.gov/about/what_are/